|

SERVICES | PAYMENT | COURSES | BOOKS | CONTACT | SEARCH |

|

|

| Christopher Warnock, Esq. |

| HOME |

|

|

|

|

|

|

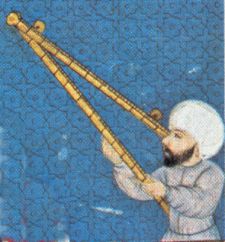

Al-Biruni

Islamic

Scientist & Astrologer |

|

Al-Biruni on the

12 Houses |

|

|

|

|

William Lilly's

Orb Table |

|

More Information on

Orbs & Aspects |